A Health Worker Raised Alarms About the Coronavirus. Then He Lost His Job.

A lawsuit by a nursing home employee in Italy will test whether health care professionals are paying a price for pointing out dangerous conditions at medical facilities.

By Emma Bubola

July 13, 2020

MILAN — In February, he said the directors of the nursing home where he worked kept him from wearing a mask, fearing it would scare patients and their families. In March, he became infected and spoke out about the coronavirus spreading through the home. In May, he was fired amid claims that he had “damaged the company’s image.”

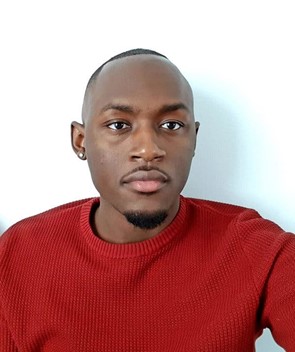

Hamala Diop, a 25-year-old medical assistant, challenged the decision in a lawsuit that was first heard in court on Monday. The proceedings will raise the issue of whether whistle-blowers have paid a price in raising alarms about dangerous conditions at medical facilities.

After successfully lowering the curve of new cases after a devastating initial outbreak, Italy is now bracing for a potential second wave.

The country, with the oldest population in Europe, was affected especially deeply by the coronavirus, and nearly half the infections reported in April happened in nursing homes, according to the Italian National Institute of Health. The breadth of the outbreak put the management of nursing homes under judicial and media scrutiny.

As the country fears the emergence of new clusters, some worry that Mr. Diop’s experience could have a chilling effect on those seeking to raise early warnings about potentially dangerous behaviors.

“Nobody protected us from catching the virus,” Mr. Diop said, “and nobody protected us from getting fired.”

On Feb. 26, as officials had already sealed off towns in the northern region of Lombardy, a director at the Palazzolo Institute of the Don Gnocchi Foundation, a nursing home in Milan where Mr. Diop worked, walked to the ward where Mr. Diop and his colleagues were tidying up the dining room. Mr. Diop said in an interview the director told them not to wear masks, that the building was safe and that they should not scare the residents. When presented with this account, the foundation said that they had always rejected any accusation that the employees were kept from using masks as “serious and baseless.”

For more than two weeks, while the coronavirus epidemic was exploding in the region, Mr. Diop said that he and his colleagues washed, changed and fed the residents without wearing masks or other protection. More than 150 residents would die in March and April, according to Milan’s prosecutors investigating the case. Asked if that figure was accurate, nursing home officials declined to comment.

“They watched TV and saw what was going on outside,” he said of the residents, “but I had to reassure them and tell them that the virus will never come into our safe place.”

Hamala Diop

The human resources director encouraged managers to place on leave employees who “polemicized” or insisted on wearing protective gear “even when they are not required to,” according to an email submitted as evidence. Mr. Diop said that he received his first mask on March 12, when more than 15,000 people in the country had already been infected and days after the government had imposed nationwide restrictions on movement and work.

That same day, Mr. Diop fell ill. A week later, his swab test came back positive for the virus. His mother, who also works at the home, was infected, too.

Eleven days after becoming sick, he filed his complaint along with 17 colleagues, most of whom also had the virus. In it, they argued that management had covered up the first coronavirus cases among the staff and prevented them from using the necessary protective gear, contributing to the spread in the nursing home.

“We are their arms and their legs and they all become like our grandpas and grandmas,” Mr. Diop said of the residents. “And they kept us from protecting them,” he said in reference to the management.

In a statement, the foundation’s lawyers said the home had followed the instructions of the Italian National Institute of Health on the use of masks, and that communications about the infections among workers took place according to privacy laws.

After news of the lawsuit was published by Italian newspapers, dozens of victims’ families filed similar complaints. Milanese prosecutors opened a criminal investigation into the home’s management. On May 7, Mr. Diop was fired by the cooperative that employed him, a subcontractor for the foundation, for talking to reporters about the lawsuit, and many of his colleagues have also been transferred or dismissed.

Mr. Diop challenged the decision, and his lawyer, Romolo Reboa, argues in court filings that Italian and European laws on whistle-blowers should protect workers who raise alarms about situations that put lives at risk. Mr. Reboa cited a similar case of a nurse in Rome who was fired after anonymously speaking on the radio about the lack of masks in his hospital.

“In nursing homes, the politics of Covid was if you speak, you get sanctioned,” Mr. Reboa said. “And this created a climate of intimidation that had a direct impact on the number of deaths.”

Mr. Diop, originally from Mali, lives with his parents and two siblings in Cormano, a small town north of Milan. He said that losing his job was a serious financial setback and that he was worried he would not find new work given his record.

While he had expected to face some consequences for his actions, he said he did not think he would lose his job, since the government had imposed a freeze on layoffs during the emergency and health care workers were particularly in demand.

“We only are heroes when they like it,” he said.